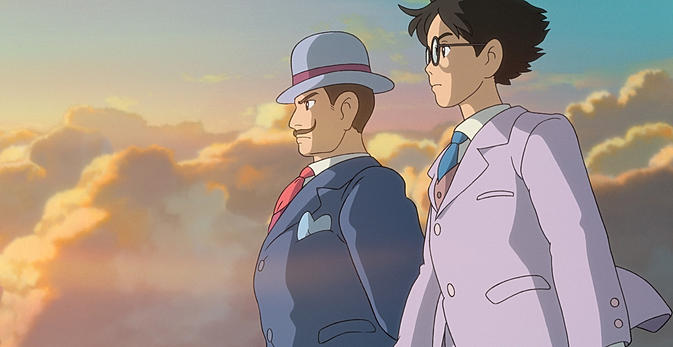

As a boy, Jiro Horikoshi dreams of becoming a pilot, however, his dreams are rendered impossible thanks to his nearsightedness. With his feverish love of aircraft still intact, Jiro shifts his goals towards Aeronautical Engineering. In Jiro’s dreams, Caproni, a legendary Italian Aircraft Designer, frequently visits him and acts as a spiritual guide which will help him along his path.

As Jiro grows older, his dreams are realized by landing a job at Mitsubishi motors. He quickly climbs the ranks to become one of Japan’s most revered engineers. His ideals are pure in intent as he retains his childhood desire to create something beautiful. But the looming dread of Japan marching into War permeates the air. Jiro’s ideals of beauty will soon be eroded into nightmares as his life’s work leads to the eventual creation of the infamous ‘Zero’ air fighters; the very same aircraft which Japanese forces used to attack Pearl Harbour.

Much has already been made with regards to the controversy surrounding the film. Some have derided the film as being “problematic” in its delivery of a message. While others have gone as far as to call it “morally repugnant” with its continued whitewashing of a war crime laden history. But to label The Wind Rises “morally repugnant” is to miss the point. For at its core, it is not a film about the politics of war. Instead, it is a human drama, a cautionary tale and a contemplative meditation about the purity of artistic intent followed by the eventual corruption of said intent.

In that traditional Miyazaki fashion, Jiro is neither a patriot nor an overt pacifist hero. His intent is not that of destruction rather it is a burning desire to create. Case in point, during an engineering meeting, Jiro optimistically states that he could remove the weaponry from one of his test planes in order to lighten the load in attempt to break the speed record. Such a “ludicrous” suggestion is met with irresponsible laughter from his peers.

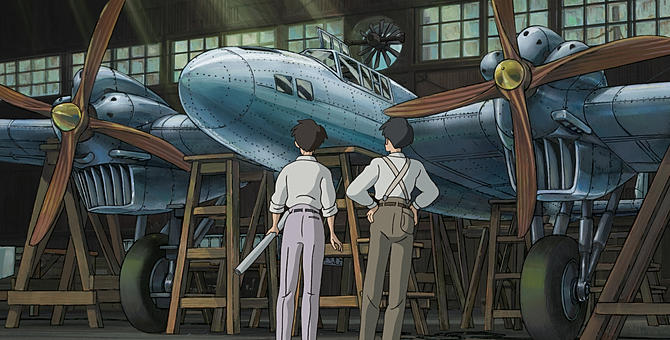

Another instance of Jiro’s true intent is exhibited when he and his colleague Hanjo pay a visit to Germany in order to research aircraft. While he sits in a lavish German warplane, he laments that it would make a better passenger aircraft then it would a war tool. In the build up to these moments, it is also lamented as to how Japan had severely fallen behind the technological curb thanks in part to the throughs of the Great Depression. It is without question that the motive for Jiro to realize his dream is strictly born of a need to progress. The yearning to break free of the old traditions and forge new ground. But unfortunately for Jiro, progression will come at a grave cost.

Jiro soon finds his ideals compromised in that selfish pursuit of realizing his dream. The film is filled with inherent irony. Early on, Hanjo states to Jiro that he should “embrace the Irony”. Embrace the Irony that having a wife at home helps you make better planes. The irony that Japan is poor yet they’re paying top dollar to design airplanes. The irony that as Jiro’s wife becomes gravely ill, his plane grows stronger.

I don’t believe this irony makes Jiro an evil person rather it humanizes him as a man whose intents are pure, but his one flaw is his tunnel vision. Which leads him down a path where his ideals will ultimately be compromised and contradicted. As Jiro grows older, his meetings with Caproni become a vocal platform to express his inner turmoil over what it is he is doing. It’s these moments where Caproni acts as not only his spiritual guide, but also his voice of reason.

Jiro is not the picture of moral perfection. Nor should he be held to such standards for he is simply human. Honestly, how many of us can say that our moral slates are clean? Do we chastise ourselves over the mistakes we have made in the past? Or do we try to learn from them and continue living onwards? In some ways, Jiro isn’t free of having blood on his hands, but on the same token it would be downright morally repugnant to expect the film to condemn one man for every last atrocity committed during wartime. Miyazaki, ever the humanist, realizes this and uses it to tell a story of personal loss and verging tragedy.

Morality in wartime is a fickle thing. I recall director Drew Goddard mentioning in the commentary track for The Cabin in the Woods that his father was a nuclear physicist who played a hand in developing numerous nuclear weapons. I cannot remember the exact quote but to paraphrase; it was along the lines of “a bunch of geniuses toiling away day to day without moral objection”. This is a statement that also rings true for soldiers situated in the front lines of war. Morality isn’t always clear and to be held to such a picture of moral perfection will ultimately consume and destroy anyone. By the evidence of this film, I would argue that perhaps Miyazaki shares a similar feeling.

Detractors have mostly questioned Miyazaki’s feigned ignorance regarding his failure to address the numerous War Crimes that Japan perpetrated during WWII. But, in fact, we must remember that the period is spanning the years leading up to the War. The plane that Jiro is designing is not the A6M rather it is the A5M. An earlier model, which took its first flight in 1934: a good three years before Japan bombed China. Therefore, the lack of concern with showing a war in motion is completely understandable on Miyazaki’s behalf.

However, this is not to say that War is ignored. War is but a looming spectre of dread permeating the atmosphere. As is often repeated, “the wind is rising”. Much like War is waiting on the Horizon. War imagery inveigles its way into Jiro’s dreams of flight. A German-Jew by the name of Castrop gives Jiro a grave warning that Japan’s ego is marching towards its own oblivion. The rise of fascism is shown as Jiro finds himself suspect of the Secret Police. While the politics remain absent, the impending war is anything but ignored. The one glimpse of true War imagery that we see is rightfully left to the tragic and bitter denouement where we leave Jiro, whom is now in his Oppenheimer-like state of regret.

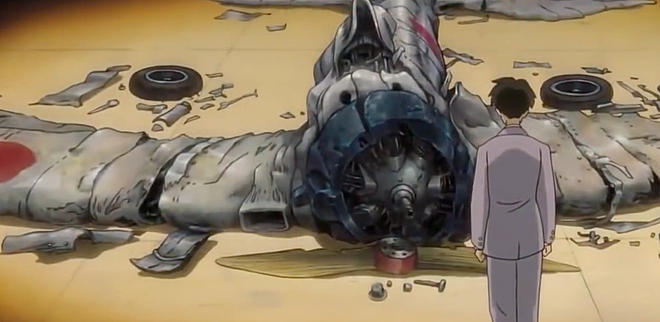

For his dream may have finally been realized, but the nightmares those dreams have bought are inescapable. The film doesn’t implicitly show the horror of what his creation bought, but those horrors are certainly suggested in poetic fashion as Jiro laments, “Everything fell apart in the end”. Perhaps it would have been more powerful to show the horrors of war. Or perhaps Miyazaki felt it would be inappropriate to potentially glorify such scenes. Perhaps he felt that the imparting message was strong enough as is. I can’t speak to his intentions, but I can say it did work for me as is presented.

If the film is guilty of glorifying anything then it isn’t the toll of destruction that the planes in question were capable of bringing. Rather it romanticises the beauty of the plane and the majesties of flight. The film exhibits a reoccurring motif. Each of the planes that take flight end existence as nothing more then a burning pile of wreckage. It’s a sharp reminder as to how something so beautiful can also bring great pain and destruction.

Some may question, “Why did Miyazaki make this movie considering he is an outspoken pacifist?” In response, some have claimed that it is a reflection of his career. To a certain extent I think this is partially true. There is a certain amount of sobering finality realized here – that is to say “if” this is his farewell. However, if we look closer into Miyazaki’s life then there are many elements of this film that hit far closer to home.

It is well documented that Miyazaki’s father was the director of ‘Miyazaki Planes’: a company, which supplied the rudders for the Zero fighter. It is also documented that whilst growing up Miyazaki clashed with his Father’s refusal to reflect on the War. However, Miyazaki also states that his father was not a Patriot and that he participated to strictly profiteer. Having known this, it becomes all the more clear as to why Miyazaki chose Jiro Horikoshi as his final subject matter. The film plays as an attempt to understand not only why Horikoshi participated, but to also meditate on what it was that Miyazaki’s father might have felt during the time.

I think it goes without saying that the film is lovingly crafted in that typical Studio Ghibli fashion. Make no mistake; this is a Ghibli film through and through. Grounded in mundane reality it may be, but it still hasn’t stopped Miyazaki from injecting his usual flavour of whimsy. Jiro’s dreamscapes play host to the grandeur fantasy. In his dreams, he is offered a ride on Caproni’s luscious new grand scale aircraft that is breathtakingly animated. While back in reality, the whimsy is kept to a subtle nature.

The titular wind plays a vital role in the romantic relationship of Jiro and Naoko. The two are serendipitously bought together by the gentle winds of fate, only to be torn apart by another gush of devastation in the form of the 1923 Great Kantô earthquake. A few years removed and they are then bought back together once again by whims of a paper plane gliding through the sky. Frolicking back and forward between the two as a form of flirtation. Their romance captures that sense of starry-eyed first love touchingly well. The hand drawn animation is once again delivered in top-notch form and these moments are nothing short of awe inspiring.

Perhaps the film is too entrenched in an eastern mentality for a western audience to fully understand. Perhaps it will alienate a large portion of its audience due to who and what it is depicting. Or perhaps it is because we here in the west still cling to the pre-conceived notion that Animation is strictly for children. And as such, we are perhaps looking for a simple clear-cut and dry moral to be imparted.

There is no moral high horse to be had. Miyazaki wavers the right and instead simply asks for your consideration. Perhaps this is too alienating for a culture that mostly expects animation to deliver simple moral values. Making this film all the more frightening since it offers no easy answers. If there is one possible technical fault with The Wind Rises then perhaps it is too subtle for its own good to be covering such topics.

I don’t believe that is the case, rather, I believe it's an incredibly honest piece of art made by an artist who is placing his own conundrums on the canvas. Or in other words, he is being completely honest with himself and in the process is asking for nothing more then our consideration.

That may be a little frightening or potentially alienating. Understandably so considering the touchy subject matter. But for myself, the audaciousness of tackling such a topic and holding no compromises captures the truest sense of what one must have felt when placed into a tough spot, such as the one that Jiro finds himself to be in. It is the harmonious marriage of both filmmaker and subject matter that makes this film so fascinating.

Miyazaki has said that he was driven to make this movie after reading a quote from the real life Jiro. “I just wanted to make something beautiful”. Much the same could be said for Miyazaki’s intention with The Wind Rises, for it is a beautiful if not challenging piece of art, one that is destined to become a misunderstood masterpiece.

This Review was Originally Posted Over at Neon Maniacs.com by yours truly

★★★★★

(out of Five)

-Daniel M

0 comments:

Post a Comment